Fake news or fair politics? Yesterday a Judge decided that Boris Johnson MP had a “misconduct in public office” case to answer for knowingly spreading fake news, while he was Mayor for London and an MP.

By repeating the statement “We send the EU £350m a week”, the allegation is that he deliberately misled the public during the Brexit vote and beyond. Ouch.

Also last week, Oxford University published its ‘Junk News during the EU Parliamentary Elections‘ report. In Poland, junk news made up 21% of all the news circulating on Twitter.

Of course, politicians have always lied.

We used to rely on independent journalists and ‘the fourth estate’ to differentiate news from opinion, but in an era of advertising-funded clickbait, social media bubbles, online global political interference and ‘mob truths’, it’s harder than ever before to identify the facts.

Or who funds the lies.

But it’s not just politicians who lie. There’s a whole cottage industry of real people and bots who deliberately set out to spread misinformation during major events.

In 2012 This tweet was widely shared (including by the White House Press Corps), and then reported as fact on CNN.

BREAKING: Confirmed flooding on NYSE. The trading floor is flooded under more than 3 feet of water.

— Comfortably Smug (@ComfortablySmug) October 30, 2012

Poor old Piers Morgan had to apologise afterwards, when the network realised it just wasn’t true.

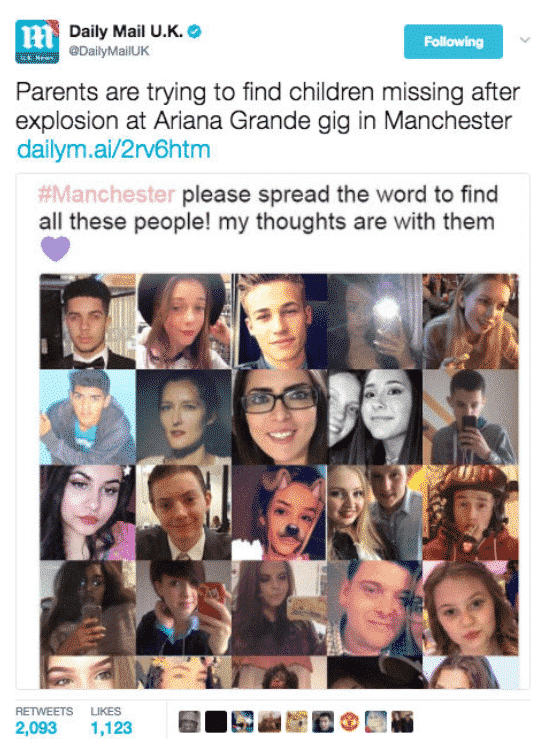

In 2017 there were a spate of ‘fake victim’ tweets following the Manchester Arena bombing and Westminster attacks.

After the Manchester bombing, the Express published a story suggesting a gunman was spotted outside Oldham Hospital, based on a rumour circulating on Facebook. But there wasn’t.

And the MailOnline published a montage of 25 ‘missing children’ – except several of the people featured were based on fake Twitter profiles, attached to fake ‘missing’ tweets.

In almost every major terrorist incident since then, misinformation has spread quickly, and been amplified by ‘traditional’ news sources, quicker to publish than to check facts.

The same is true with pretty much ever political incident too.

Just last week the former Mayor of New York, Rudy Guilliani (currently Donald Trump’s lawyer) tweeted a link to a distorted video which set out to make Nancy Pelosi’s speech sound deliberately slurred.

When lawyers, politicians, and journalists clearly can’t cope (or just don’t want to), how can businesses spot fake news?

Dealing with fake news is increasingly a part of the crisis communications training sessions that we run. We tend to take a BBC approach and encourage organisations to rely on one ‘official’ or two independently verifiable sources before believing anything to be true.

There are (expensive) global tools available – like Dataminr, Geofeedia, Echosec and others, but many organisations don’t need or can’t afford their subscriptions.

We look at some of the free tools below.

How to verify facts in an era of fake news?

As we all know there are lies, damned lies and statistics. One person’s expert opinion is another person’s project fear etc. etc. We can possibly rely on the courts (in the case of Boris Johnson above), or organisations like Full Fact (in the UK).

With the exception of politics perhaps, there’s no escaping the need for some decent detective work on social channels, alongside sourcing accurate information from trusted sources on the ground.

How to verify Twitter accounts to spot the bots?

One of the best tools to peak under the bonnet of Twitter accounts is the account analysis tool by Luca Hammer – it can’t ‘prove’ anything, but will give a lot of clues about how often the account tweets, who to, what interfaces they use, frequency etc.

Clue – if an account is either brand new, never replies (or posts), only ever uses the same interface, and is as busy in the middle of the night as the middle of the day, be suspicious…

Other good tools include Treeverse to visualise the history of conversations/threads, and twlets (paid), which lets you build a spreadsheet of any user’s Tweets.

How to verify photographs?

There are two main ways to verify images – by exif data (which often includes time/date/location information) or by origination (to compare two images, maybe to see which was published first, and when). There are number of tools to help with both including Phil Harvey’s Exif Tool for Exif Data and Google’s reverse image search or TinEye for image-comparison.

Look for when/where the original photo was taken, and where it was first published.

How to verify videos?

We’re about to hit an era of deep fake videos, and the verification tools will take time to catch up. But until they do, tools like Invid will remain invaluable for helping to analyse any associated metadata, comments, keyframes, reverse-images etc.

Invid’s Magnifier lens is not quite Bladerunner but not far off. It will help identify signs, banners and any other written words.

Amnesty’s Youtube Dataviewer is also good for films on YouTube.

And tools like Google Earth, Wikimapia and Suncalc can also help pinpoint location and/or debunk the implied timings.

And once the facts are clear…that’s when the communications strategy comes into play…

Further Reading

Department of Homeland Security – Countering False Information on Social Media in Disasters and Emergencies

BBC College of Journalism – UGC expertise can no longer be a niche newsroom skill

Poynter Institute Fact Checking Today website

🇬🇧 Oxford University’s Computational Propaganda Project – Algortihms, Automation and Digital Politics